Show #1: PETE SEEGER - Full Audio & Transcript

Go to the Master List of Shows (Home Page)

The following interview with folk music legend Pete Seeger was broadcast April 30 and May 4, 1963 from New York City on worldwide short-wave radio. This historic radio interview was transmitted from the studios of Radio New York Worldwide on the show Folk Music Worldwide hosted by newsman Alan Wasser.

Featuring five song performances: "Oh! Liza, Poor Gal"; "Good Night, Irene"; "Wimoweh"; "Follow the Drinking Gourd"; and "Barbra Allen". Transcript includes full song lyrics.

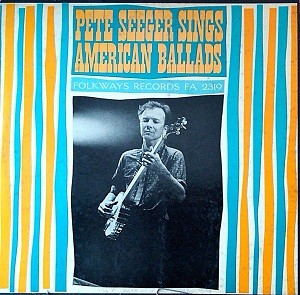

American Ballads by Pete Seeger

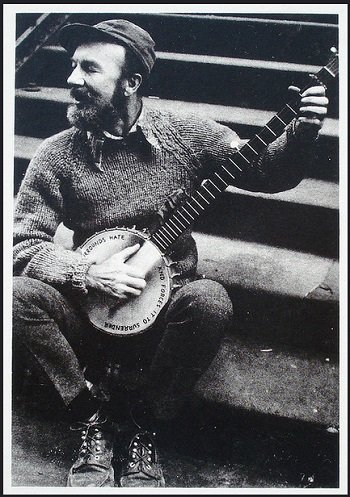

photo: Alan Wasser

Listen to the Show

Transcript:

MEL BERNAM (ANNOUNCER): Here is Radio New York Folk Music Worldwide. A program devoted to the best in folk music throughout the world. Showcasing the top performers and authorities in the field. Now your host for Folk Music Worldwide, Alan Wasser.

ALAN WASSER (HOST): We're privileged to have in our studios today the man who Alan Lomax calls "the best all-around folk performer," Mr. Peter Seeger.

We will listen to some of Mr. Seeger's recordings, and we'll be talking with him about his life, his songs, and folk music in general.

Mr. Seeger, the obvious first question is, just how do you define folk music?

PETE SEEGER (GUEST): I think you have to accept the fact that hardly any two people, not even the experts, agree on a definition.

You see, way back in the old days, say in Europe of the Middle Ages, you had an aristocracy, and they could afford to pay for musicians. The kings and queens had musicians in the castles, and that developed into symphony orchestras and what we call "Classical music" now.

But folks out in the country couldn't afford to pay for anybody else to make music. They had to make their own. So the peasantry had their music, and it was about a hundred years ago given the name "Folk music".

In the United States, many people said you can't have folk music in the United States because you don't have any peasant class. But the funny thing was, there were literally thousands, tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands of people who loved old time fiddling, ballads, banjo tunes, blues played on the guitar, spirituals and gospel hymns.

These songs and music didn't fit into any neat category of art music nor popular music nor jazz. So gradually they said well let's call it folk music.

But as I say, no two people agree on the term. I don't argue about it myself.

It's like two people arguing abut the definition of beer. Now you put a glass of New York beer in front of a Londoner and he spits it out. Phew, that cold tasteless stuff. Bring me some beer!

Now you put a glass of London beer in front of a New Yorker, and he'll spit it out. You mean that warm, sour stuff? Bring me some beer.

I don't get into an argument. If I'm in London, why I'll drink the beer there, and if I'm in New York I'll drink the beer there. But I don't get into an argument about the definition.

ALAN: How did you first actually get interested in folk music?

PETE SEEGER: I was about 16 years old back in 1935, and my father was a professor of musicology. He took me down to a square dance festival down in North Carolina.

For the first time in my life, I found there was music in my country that you never heard on the radio, and you didn't hear on the juke boxes, and in theaters. I fell in love with it, especially the long-necked banjos.

As a matter of fact, let me ask you to play one of the first tunes I learned back in those days. It's a mountain banjo tune called Oh! Liza, Poor Gal.

ALAN: Let's hear that now.

(Song performance 1 of 5: "Oh! Liza, Poor Gal" by Pete Seeger):

Lyrics:

Oh Liza poor gal, Oh Liza Jane.

Oh Liza poor gal, she died on the train.

I'm going up on the mountaintop, plant me a patch of cane.

I'm gonna make molasses to sweeten Liza Jane.Oh Liza poor gal, Oh Liza Jane.

Oh Liza poor gal, she died on the train.

You go down that old fenced road,

I'll go down the lane.

You can hug an old fence post,

I'll hug Liza Jane.Oh Liza poor gal, Oh Liza Jane.

Oh Liza poor gal, she died on the train.

Oh Liza poor gal, Oh Liza Jane.

Oh Liza poor gal, she died on the train.

[end of music]

PETE SEEGER: The banjo was originally an African instrument. Then, in the Southern plantations, the slaves figured a new way of playing it, which was half European and half African.

Around the year 1830, the banjo was picked up by white people, and it swept America just like Rock 'N' Roll music did 100 years later.

Banjos were everywhere. A man could make one himself. They went West in the covered wagons. Then it kind of died out as popular music styles changed.

Then, in the 1930's when I was a teenager, I wanted to learn it. The only place I could learn it was back in the hills.

When I got out of school, I spent two years just hitchhiking around. Every time I met some old farmer who could play it, I got him to teach me a lick or two. Little by little, I put it together.

ALAN: Where did you go from there?

PETE SEEGER: I never intended to make a living from it. That's the funny thing. I wanted to be a journalist.

But I couldn't get a job as one. I remember one editor telling me, he says, "Young man, I had to lay off one of my best reporters last week. You expect me to hire you, and you've had no experience?"

So I used to pick up change, mostly singing in schools, summer camps, and places like that. By and by, the kids grew up and went to college. Ten years ago, I used to get requests from college students to come out and sing for them.

Lo and behold, it's now developed into a big commercial field as dozens of performers putting on hundreds of concerts, thousands of them perhaps, every year in the thousands of American universities and colleges. People like Odetta, Richard Dyer-Bennet, and the Kingston Trio, of course.

What I'm especially happy about is that at last the college students have finally realized some of the very best folk musicians are real country people.

ALAN: I understand you knew Lead Belly, the famous old folk singer.

PETE SEEGER: Yeah, and when I stop to think of it, he was my main music teacher although he didn't know it. I'd follow him around and watch his hands closely. I admired him so.

I remember someone once saying, "Pete, you know you really should take voice lessons." And I said, "Well, if I could find any voice teacher that could teach me to sing like Lead Belly I'd spend every cent to study under him."

But every time you'd go to a voice teacher, he'd teach you to warble, as if you'd want to be an opera singer, and that's not what I'm interested in.

Lead Belly died in 1949, but he taught us some of the best songs we'll ever know. He never made any great deal of money out of his music. But I think he'll live forever in the young people who are singing his songs, like Rock Island Line, Old Cotton Fields at Home, Midnight Special, Bring Me Little Water Sylvie.

Come to think of it, the first hit record that I and The Weavers ever had was his theme song. People ought to hear it now. It's Good Night, Irene.

(Song performance 2 of 5: "Good Night, Irene" by The Weavers):

Lyrics:

Well, Irene goodnight, Irene Goodnight.

Goodnight Irene, Goodnight Irene, I'll see you in my dreams.Last Saturday night I got married.

Me and my wife settled down.

Now me and my wife are parted.

I'm gonna take another stroll downtown.Let me hear it now. Irene goodnight. Irene goodnight.

Goodnight Irene. Goodnight Irene. I'll see you in my dreams.Sometimes I live in the country.

Sometimes I live in town.

Sometimes I take a great notion.

To jump into the river and drown.Well Irene goodnight.

{Try some harmony.}

Irene goodnight. Goodnight Irene.

Goodnight Irene. I'll see you in my dreams.You caused me to weep,

You caused me to moan,

You caused me to leave my home.

But the very last words I heard her say,

Was please sing me one more song.

[end of music]

ALAN: That's quite a song, it really is. This recording we have, it was with The Weavers?

PETE SEEGER: This was a Carnegie Hall concert of 1955. The members of The Weavers are two New Yorkers, Ronnie Gilbert with a vibrant alto voice, Fred Hellerman with a kind of low baritone, and Lee Hayes who used to be a preacher in Arkansas with a kind of a bass.

Me, I'm a split tenor.

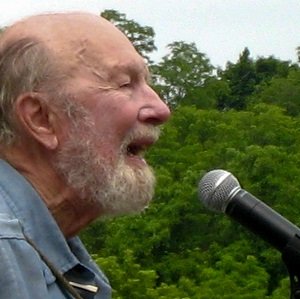

Pete Seeger in 2007, leading a sing-a-long

at The Great Hudson River Revival

(also known as The Clearwater Festival)

flickr / Paul VanDerWerf

ALAN: What's a "split tenor"?

PETE SEEGER: I sometimes sing in falsetto - sometimes high, sometimes growl. I don't really have a voice as you can tell right now. I get by mostly by default.

The Weavers showed that folk music could be good entertainment in the cities. And following them came the Kingston Trio, and the Gateway Singers, and half a dozen others. Peter, Paul & Mary are the latest ones.

They're all friends of ours. Mary Travers in Peter, Paul & Mary was in a little singing group I had here in New York, when she was just a high school student.

ALAN: Really? I can see why they consider you the patriarch of folk music.

PETE SEEGER: It's a terrible thing being a patriarch. I don't even have a gray beard. But people keep calling me up for advice.

Try as I may to tell them I'm no authority, and that I can't even give advice to my own children - at least they don't take it - nevertheless I sometimes get called a "high priest" or "dean". What worse names could you call people?

ALAN: Speaking of your family, you're a whole family of folk singers these days, aren't they.

PETE SEEGER: My father married twice, and I'm the youngest of the first batch. Michael Seeger and Peggy Seeger are the oldest of the second batch.

They're wonderful musicians. I think Mike is one of the greatest instrumentalists I've ever heard in my life. I think Peggy is one of the greatest ballad singers I've ever heard in my life.

She's married to Ewen McCall, an English folk singer now. She's subject to Her Majesty over there.

I have three children myself. My wife and I and the three of them plan to take off this summer and visit some different parts of the world. Perhaps we'll come to some of the countries where some of your listeners are.

ALAN: Which countries?

PETE SEEGER: In September we'll be in Australia and New Zealand. In October and November we'll be in Japan.

I don't know what exactly short stops we'll make between, but we'll be in India around December and in several African countries during January. In February we'll be in Italy and during March and April and May other countries in Europe.

ALAN: On these tours, I've always wondered, do you get more songs than you sing, or is it the other way around?

PETE SEEGER: I have to resist the temptation to want to learn everything. You know, you can't.

You have to restrict yourself at some time, or else you find yourself just being spread too thin. And already I think I try too many things.

Occasionally I'll sing a song from Japan, or try and make my banjo sound like a sitar from India, or some Eastern European dance, or an Israeli song.

One of the first hit records The Weavers had was Tzena, Tzena from Israel. As a matter of fact, one of my all-time favorite songs is a song from South Africa.

I learned it off a phonograph record about 12 or 13 years ago. I had a cold, as I have now. I was in bed. I listened to this record over and over, admiring it. Suddenly I realized it was quite simple.

The basses did the same thing over and over again. The tenors did the same thing over and over again. And the fellow singing falsetto did.

So I tried learning it. I didn't think I could hit that high note until I just screwed up my courage, took a deep breath, opened my mouth up wide and let it out.

Sure enough, I hit it. It's the highest note I'm able to hit.

But this song, which I originally did as a novelty, ended up being not only one of my favorites but I think other people's favorites too.

Here it is, with The Weavers helping out. It called Wimoweh. Down in South Africa, it's "Mbube" which means "the lion".

(Song performance 3 of 5: "Wimoweh", Pete Seeger and the Weavers):

Lyrics:

Oh way up high, a wimoweh, a wimoweh, a wimoweh, a wimoweh

way up high, a wimoweh, a wimoweh, a wimoweh, a wimowehA wimoweh, a wimoweh, way up high, a wimoweh, a wimoweh

ah, ah, ah ah a wimoweh, a wimoweh, a wimoweh, a wimoweh(etc.)

[end of music]

ALAN: Incidentally what does that mean?

PETE SEEGER: People often ask me what songs mean. It's important. These songs do mean something.

There's a story behind every old ballad or work song or nonsense song that I ever knew. Sometimes it's a fascinating story. A story of people struggling for freedom, struggling to get along in this old world.

This particular song - of course, I've never been to South Africa - but I found out it means one phrase: "The lion is sleeping. The lion, the lion, the lion. The lion is sleeping. The lion, the lion, the lion."

What would that mean? I think you'd have to be in South Africa to realize exactly what it means.

The last king of the Zulu people was a great military chieftain named Chaka the Lion. After he was killed and the Europeans took over that part of the world the legend arose, as I'm sure it has in other parts of the world, that Chaka the Lion was not dead. He simply went to sleep and would wake up sometime to lead his people to freedom.

Think of what's going on in South Africa today, and think why this song was so powerful.

ALAN: There's another song with a similar background I imagine that has always confused me: Follow the Drinking Gourd.

PETE SEEGER: Back in the 1850's there were some very brave Americans who risked their lives to try and help slaves escape from the South to freedom in Canada. This song comes from that period.

It consists of some new words to an old Methodist hymn. The Methodist song was called Follow the Risen Lord.

(Song performance 4 of 5: "Follow the Drinking Gourd" by The Weavers):

Lyrics:

Follow the Drinking Gourd.

Follow the Drinking Gourd.

For the old man is a waiting for to carry you to freedom.

Follow the drinking gourd.Now when the sun comes back and the first quail calls.

Follow the drinking gourd.

The old man is a waiting for to carry you to freedom.

Follow the drinking gourd.Follow the drinking gourd.

Follow the drinking gourd.

For the old man is a waiting for to carry you to freedom.

Follow the drinking gourd.Now the river bank will make a mighty good road.

The dead trees will show you the way.

Left foot, peg foot, traveling on.

Follow the drinking gourd.Follow the drinking gourd.

Follow the drinking gourd.

For the old man is a waiting for to carry you to freedom.

Follow the drinking gourd.Now the river ends between two hills.

Follow the drinking gourd.

There's another river on the other side.

Follow the drinking gourd.Follow the drinking gourd.

Follow the drinking gourd.

For the old man is a waiting for to carry you to freedom.

Follow the drinking gourd.

[end of music]

PETE SEEGER: At some point somebody changed the words slightly. You can imagine the slaves singing it in the fields.

The overseer comes down with his whip and says, "Well, I like to hear them all singing. That means they're all happy." And there they were singing a song which was giving a time table and a set of directions for slaves to escape to the North.

The "drinking gourd", of course, is double talk for the Big Dipper which is in the north sky pointing to the North Star and where freedom was.

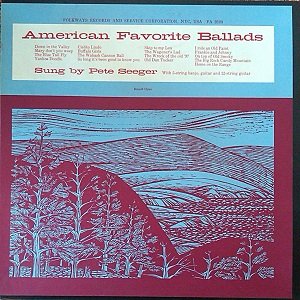

American Favorite Ballads by Pete Seeger

photo: Alan Wasser

Of course, it's a little bit dangerous to always assume that you know exactly what the meanings of a song are. It's interesting, though, to analyze what meanings could be.

For example, one of the most favorite of all the old English ballads is a song called Barbara Allen. I've heard scholars discuss for hours on end why that song should be more popular than any other ballad that ever came here from England.

Is it because the men are trying to prove how cruel the girls are? You know, she won't even give him one last kiss so he dies for love of her.

On the other hand, do they like it simply because it's a beautiful melody? But there are several different melodies used for it.

Do they like it because it's beautiful poetry? Hardly any one verse is found in every version. Everybody's got their own way of singing it.

One verse, however, is always included. It's the last verse, which describes the brier growing out of the grave of Barbara Allen, the cruel girl, and the red rose growing out of the grave of Sweet William, the boy who died for love of her.

It describes them going up the wall and intertwining at the top in a lover's knot.

You listen to the song, and at the end I'll tell you what my interpretation of that is.

(Song performance 5 of 5: "Barbra Allen" by Pete Seeger):

Lyrics:

In Scarlet town where I was born,

There was a fair maid dwellin'.

Made many a youth cry well a day.

And her name was Barbara Allen.'Twas in the merry month of May.

When green buds they were swellin'.

Sweet William came from the west country.

And he courted Barbara Allen.He sent his servant unto her.

To the place where she was dwellin'.

Said my master's sick, bids me call for you.

If your name be Barbara Allen.Well slowly, slowly got she up.

And slowly went she neigh him.

But all she said as she passed his bed.

Young man, I think you're dying.Then lightly tripped she down the stair.

She heard those church bells tolling.

And each bell seemed to say as it tolled.

Hard hearted Barbara Allen.Oh mother, mother go make my bed.

And make it long and narrow.

Sweet William died for me today.

I'll die for him tomorrow.They buried Barbara in the old church yard.

They buried sweet William beside her.

Out of his grave grew a red red rose.

And out of hers a briar.They grew and grew up the old church wall.

'Til they could grow no higher.

And out the top, twined in a lovers knot,

A red rose and the briar.

[end of music]

PETE SEEGER: I think it means that everybody in this world at some time experiences cruelty or perhaps is cruel, and regrets it. This song holds out some kind of sublimated hope that maybe there'll be reconciliation in some way. Either in this world or the next or somewhere.

ALAN: I'm afraid our time is up. Mr. Seeger, I can't tell you how much we appreciate your coming in and being our guest.

MEL BERNAM (ANNOUNCER): This has been Folk Music Worldwide. Devoted to the best in folk music throughout the world and spotlighting top performers and authorities in the field. If you have any suggestions, request requests or comments why not write in to Folk Music Worldwide, Radio New York WRUL, New York City 19 USA. This has been a Music Worldwide presentation of Radio New York Worldwide.

Go to the Master List of Shows (Home Page)